In the 1830s a number of ships were wrecked in Algoa Bay. They included the Kate in 1834 (Captain E Cattell), Cape Breton 1835, and Fee Jee 1837 (Captain W Bewley). All these wrecks were the result of south-easterly gales, a reminder that in the face of on-shore winds, sailing vessels within a harbour were at the mercy of the elements, frequently lost their anchors and were driven ashore. An additional problem was that some ships were in poor condition with rusted cables and other defects.

The 1840s were equally disastrous, reports of shipwrecks in Algoa Bay being a regular feature of the Graham’s Town Journal. Captain James Caithness of the schooner Mary lost his ship in March 1844 during a south-easter on her way back from Mauritius. Her cargo of sugar, rice and dates was saved as were all on board, but Caithness was an unlucky mariner for he also lost the Lady Leith four years later. See:

http://molegenealogy.blogspot.com/2013/06/wreck-of-lady-leith-1848.html

|

| Shipping Intelligence: South African Commercial Advertiser 16 December 1837 Note mention of Conch and Bell and numerous other ships. Click on pic to zoom. |

Why men like the Caithnesses, Scorey and Bell should choose such an unpredictable and dangerous career as that of mariner along the beautiful but deadly coast of South Africa is an unanswerable question. Perhaps they were born sailors. No matter how skilled and experienced they may have been, they couldn’t control the weather or make the wind blow in the right direction – if it blew at all. Many a ship was wrecked when the wind failed and this is what happened to the Conch in 1847 when she came to grief at Port St Johns. Bell was not in command of the schooner at the time (a Captain W Moses had that dubious honour).

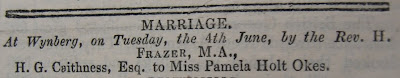

From 1837, when Bell first appears in the records as captain of the Conch, his life was packed with incident and adventure, not to mention domestic events such as marriage in 1838 followed by the baptisms, at regular intervals, of his numerous progeny. It is uncertain how Bell managed to support this brood as a maritime career wasn’t lucrative and was subject to fluctuating circumstances.

EXTERNAL INFLUENCES

Contributing factors were not only the weather and the usual hazards of a coastal mariner’s existence. It’s important to remember that an ancestor did not live in a vacuum. Beyond his private and professional life there was the Big Picture: the backdrop to his own small drama. In Bell’s case, matters beyond his control included the Colony’s economic well-being and the state of trade, politics and Government, and whether there was Peace or War. Since – and indeed before - the arrival of the British immigrants now known collectively as the 1820 Settlers, there had been continual unrest on the Colony’s eastern frontier and this showed no sign of diminishing as that decade, and then the next, passed.

|

| Troops on the Eastern Cape Frontier |

H G Caithness, as captain of the Fame, was recorded in the Cape Frontier Times, published at Graham’s Town, in November 1840 carrying from Table Bay to Algoa Bay the following passengers: Colonel MacPherson, Captain and Mrs Lonsdale and family, 29 Soldiers, 10 women and 28 children. The rank and file (i.e. ‘29 soldiers’) were as usual not named, though their officers were as was the Captain’s wife. All these would have been part of the military establishment. Considering that the Fame was a schooner, the passage – which in this case took 8 days so the weather can’t have been in their favour - was doubtless an uncomfortable one for the 70 souls packed on board (not including the crew). The responsibility of Caithness as master on such a voyage can be fully appreciated.

The increased volume of shipping at Cape ports would continue during the Seventh Frontier War (the War of the Axe) in 1846-7. Meanwhile, from 1834 the move away from the Cape of about 15,000 Afrikaner frontiersmen, later called the Voortrekkers, was in progress. Bell could not have foreseen how this exodus would impact his own career.

CALM SEAS

William Bell and Conch continued to ply the coastal ports during the early 1840s and it is possible to track their activities by references in local newspapers.

In September 1841 the Cape Frontier Times mentions, ‘Conch schooner, W Bell, (departing) Table Bay 5.9.1841, (arriving) Algoa Bay 7.9.1841 (a remarkably quick run); Passengers: Rev Mr and Mrs Taylor, Mrs Stonelake, Mr and Mrs Ziervogel, Mr Scorey, Mr Matthew, 2 children and 6 in steerage. (Note the habitual omission of names of steerage passengers.) The inclusion of Scorey tells us that Bell apparently wasn’t averse to carrying on board members of his wife’s family: this individual may have been James Scorey, uncle of Mary Ann Bell and master of the schooner Flamingo during the 1820s and early 1830s, though the Cape Government Gazette at the time also referred to other Scoreys, initials S, F and G. It is an unusual surname and they were all likely to have been related.

|

| Schooner |

A more important personal event was the birth of William and Mary Ann’s first son, William Douglas Bell (usually called Douglas to avoid confusion with his father); all seemed well on the domestic front. However, the comparatively calm waters in which Bell was then sailing were threatened by some unexpected storms ahead. All of Bell's courage and experience were to be put to the test.

To read from the beginning of this series of posts go to:

http://molegenealogy.blogspot.com/2013/06/coastal-ships-mariners-and-visitors.html

.jpg)