Daniel Woodriff, born in 1756, went to sea at the age of six

as servant to master gunner George Woodriff, his uncle. In December 1767 he was

admitted to the Royal Hospital School Greenwich and later apprenticed to a

merchant captain in the Jamaica

trade. In 1778 Woodriff was pressed into the navy, and by 1782 was promoted

lieutenant. After eleven years on the American Station and in the West Indies

he returned to England. He made his first trip to Australia in 1792 in the ship Kitty, with

supplies and convicts, and reported on Port Jackson’s naval defences. He was

promoted commander and 1803 saw him once again bound for Australia: he had been appointed to command HMS

Calcutta on Daniel Collins’s expedition to found a British settlement in the Bass Strait.

|

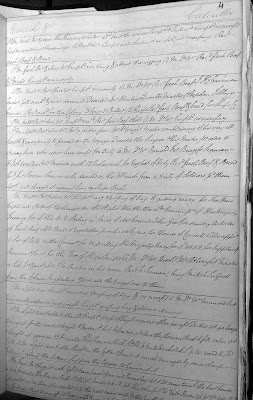

| Page from Woodriff's log |

During the first leg of this voyage, his ship had separated from her companion vessel, Ocean, at

Tristan da Cunha and by 15 August 1803 Woodriff noted in his log that the Calcutta was moored in Simon’s Bay near the Cape of Good Hope, having made the run from Rio in 24 days. His meticulous account brings into

sharp focus the everyday activities on board, reminding us that a ship was a floating village and that crew members were versatile in their skills.

On 16 August, it was business as usual, the people ‘employed

in watering and brooming. Carpenters building pens and stables for cattle.

Sailors making bags for hay. Sail’d the mercht ship Thomas of London for

Desolation* … Deserted John Brown and R Southey Seamen … Received fresh beef and

bread.’

Evidently Woodriff ran a tight ship and didn’t flinch from

maintaining discipline in the best naval tradition. His log entry for 21 August

reveals that Brown, the seaman who had deserted, was promptly returned to the

vessel having been apprehended by a party of soldiers whom Woodriff paid forty

shillings for their trouble, the amount being charged against the deserter on

the Ship’s Books. Further reprisals were visited on Burgess, a seaman, and a Marine

named Woolley, who received 12 lashes each for neglect of duty.

At this point synchronicity comes into play.

|

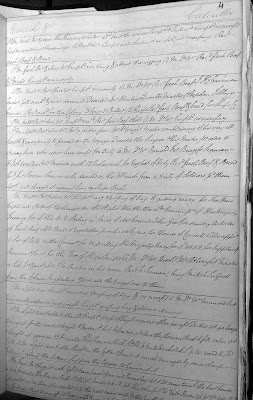

| 'Received 6 Seamen being British subjects from the Johanna Magdalena ....' |

Monday 22 August: ‘Moderate Breeze and clear. Employed

receiving and pressing of hay and getting ready for Sea. … Died Mr Richard

Wright, Master … Received 6 Seamen being

British subjects from the Johanna Magdalena and procured the Wages due to

them.’

One of these men was James Caithness. Robert Knopwood’s

diary, written during the same voyage, also mentions

the British volunteers who were taken on to Calcutta’s complement at Simon’s

Bay. However, Woodriff provides an important additional detail - that

these six seamen, including Caithness, had previously been on the Johanna

Magdalena. This vessel was originally known as the Prince William Henry but had

a change of name and flag when she was taken over by the Dutch.

If James Caithness hadn’t been at Simon’s Bay while Calcutta was at anchor he would have missed out on an

exciting adventure to Australia

and a chance to sail round the world. On the other hand he wouldn’t

have been among those captured on Calcutta

in 1805 and sent to a French prison. The lives of Woodriff and Caithness were linked by Fate.

The useful reference to the ship Johanna Magdalena (aka

Prince William Henry) in Woodriff’s log offers an avenue for further research

into James Caithness’s career.

|

Simonstown: Then and Now |

* Possibly Kerguelen Islands in southern Indian Ocean.

Acknowledgement:

Tom Sheldon