Life in Victorian times was a tough undertaking; many men ‘escaped’ into the Army which was only marginally better in conditions and attitude. Christmas Day occurs every year and so Christmas Day 1879 dawned for the 2nd Btn Rutlandshires. Every season has its own sense of importance but preparations for this day of days takes a special turn in attitude and feeling. The officer class and enlisted men largely drop their class differences and become soldiers in barracks at Christmas. The General Return Of the Army in Victorian times shows some 223,000 enlisted men and many of these saw service in foreign lands for up to 20 years or so.

Differences between the officers and men were relaxed to a certain extent and preparations were underway for Dec 25th. Christmas Day in the Army was characteristically an organised affair with nothing left to chance. An air of solemnity was observed in the traditions of this day. Each man had a heavy burden of individual responsibility. Large quantities of both liquid and solid refreshments were procured, a great change from the Spartan diet usually endured by the men at this time.

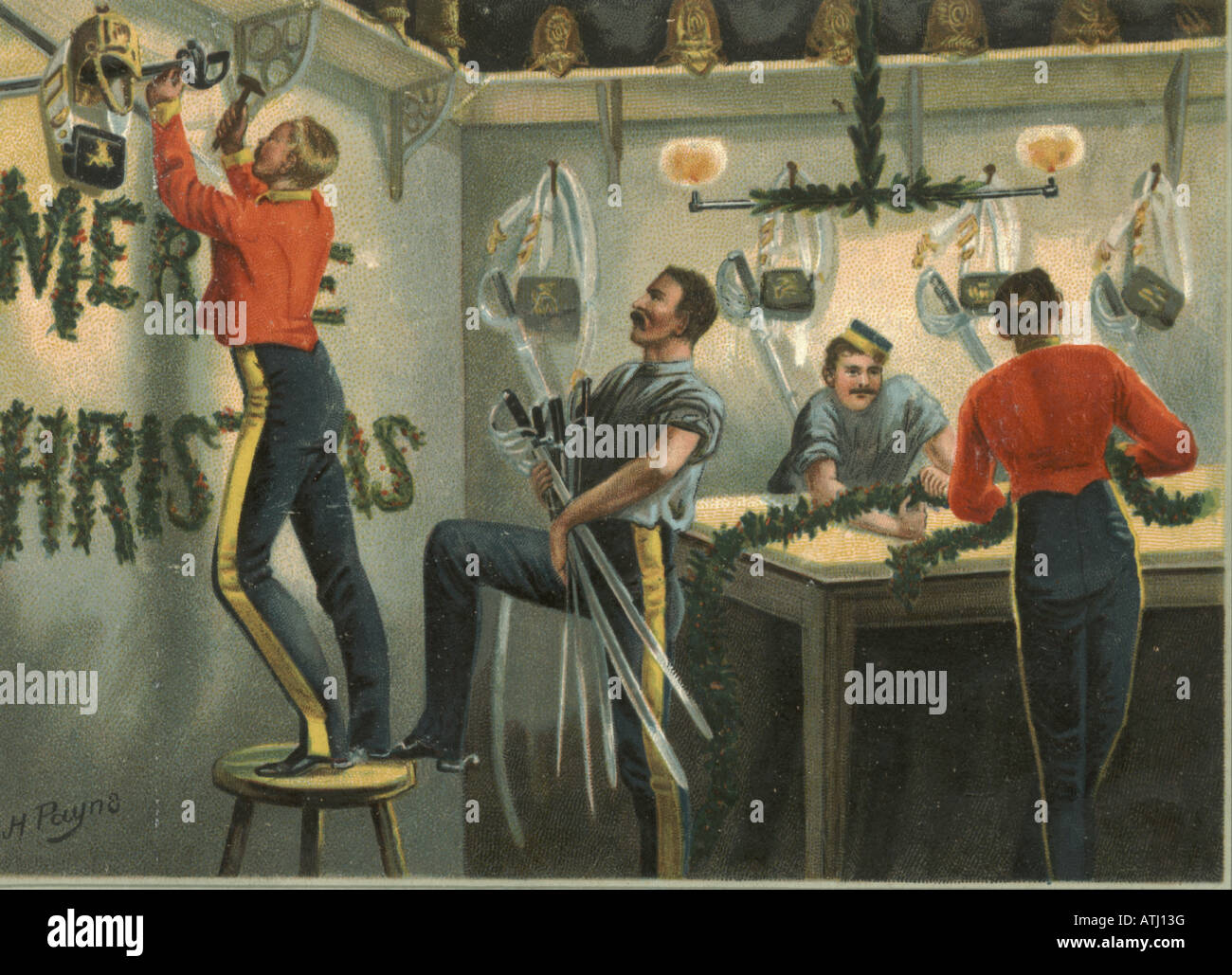

The officers added to the fund with game and many a bottle to fuel the festive gatherings. The canteen funds swelled as this day approached. Barrels of ale, stout and porter appeared along with wine but little or no spirits. These supplies were taken in charge by the Colour Sergeant of each company and kept under lock and key until lunch on the 25th. As the great day loomed closer, the men were seen undertaking many a festive activity - stoning raisins for the puddings, divesting goose, duck and turkey of feathers, fashioning festoons of coloured paper and wreaths of holly. Men were detailed to act as messengers between the cookhouse and men’s barracks, the cooks having risen at an unseemly hour to make good the food to be served later in the day. At 6am reveille sounded on the barrack square by the duty bugler: Christmas Day had arrived!

Even before the last note had died away in the frosty air, the barracks of some 700 men were already a hive of activity, lights twinkling from many windows, scores of men moving along dimly lit passages to perform their necessary ablutions, once completed the rooms swept clean and dusted, beds made up as laid down in standing orders (I love that line). No drill today but Army Sunday routine observed. Once breakfast is over Church Parade takes over. ‘Fall In’ occurs at 10.30 am, many a soldier, though, being fortunate to have leave with families elsewhere. Today there are 350 men attending the Garrison Church, once everyone is inside the Chaplain commences the service. Being a former soldier himself he knows that a long service would not be the thing and delivers a more cheerful sermon than is usual.

On conclusion of the service the men are marched back to their barracks and dismissed, during their absence ‘cook’s mates’ have been busy getting the food ready, tables decorated, ceilings and walls gaily garnished with festive decorations. Much liquid of a beer nature is seen in every room. At 20 minutes to one the peal of the bugler playing ‘Come to the cookhouse doors me lads’ can be heard and the designated orderlies rush to the cookhouse to receive from their company cooks the food allocated to each mess. A batch of helpers is carving and serving up the now eagerly sought-after food. Food is taken to those on duty, and at one o’clock the bugle sounds again and the men sit down to start the feast.

Junior NCOs act as waiters to their comrades; cheerful demands for more turkey and duck ring out amongst the popping of corks and consumption of ale, beer barrels rapidly emptying. In comes the Company Colour Sergeant and calls ‘Attention!’, his keen ears having heard the clink of sword and spur on concrete floor: this heralds the visit of the Colonel, his adjutant and duty officer of the day. The Colonel wishes the men a Happy Christmas and turns to leave, this is the cue the Colour Sergeant was waiting for, as was the Colonel, knowing the procedure from past Christmases in the barracks.

‘Beg pardon, sir, the men would like to drink your health’. ‘Thank you, Colour Sergeant’. ‘Sherry or port, sir?’ - advancing to the two black bottles put aside for this very purpose, trying to recall what each one contained. ‘Whatever comes first, Colour Sergeant,’ retorts the Col. ‘Just a little though, if you please’, knowing he and his party will go through this more than once today. ‘A Company Attention!’ bellows the Colour Sergeant in a stentorian voice, ‘I propose the good health and long life of the Colonel and all the officers. Pte Jones, keep your hands off that plum duff for half a minute.’ Many heartfelt epithets are sounded, the Colonel is well loved by his men and his reply follows: ‘Men of A Company 2nd Rutlandshires, I am much gratified at the honour you have bestowed on me, enjoy yourselves and have a very happy Christmas.’ At this point he picks up his sword and leaves with his party to the next Company where this is repeated once again.

A great deal of toasting and well wishing continues throughout the day. Pte Jones tucks into his plum duff barely looking at the falling snow which appeared as if on cue. The Colonel retires to his quarters as do the officers and Sergeants to celebrate the Festive Day in their own manner. Much smoking and merriment ensue from the men, singers are encouraged to exercise their talents and problems are forgotten. At nightfall some of the men get into walking out dress and pursue the taverns of the town, the barracks now largely deserted. At 9:30 pm a roll call is taken and three quarters of an hour later the duty bugler plays ‘Lights Out’ on a crisp and white barrack square, thus proclaiming the official end to Christmas Day 1879.

Article by Graham Mason, Zulu War researcher and specialist.

No comments:

Post a Comment