|

| South African Commercial Advertiser 16 Dec 1837 |

Pages

Showing posts with label mariners. Show all posts

Showing posts with label mariners. Show all posts

Sunday, May 28, 2017

Friday, January 24, 2014

Mole's Genealogy Blog Top Ten

Most popular posts:

More on Anglo-Boer War Ancestors

molegenealogy.blogspot.com/2010/03/more-on-anglo-boer-war-ancestors.html

19th c German Immigrants in South Africa

molegenealogy.blogspot.com/2010/02/more-19th-c-german-immigrants-in-south.html

Pruning the Family Tree

molegenealogy.blogspot.com/2011/07/pruning-family-tree.html

Passenger Lists as a Primary Source

molegenealogy.blogspot.com/2011/06/passenger-lists-as-primary-source-in-sa.html

Your Ancestor in the South African Constabulary

molegenealogy.blogspot.com/2010/03/your-ancestor-in-south-african.html

Identifying Uniforms in Photographs

molegenealogy.blogspot.com/2010/03/identifying-uniforms-in-photographs.html

Passengers to Natal 1865

molegenealogy.blogspot.com/2012/06/passengers-to-natal-1865.html

19th c Immigration to South Africa

molegenealogy.blogspot.com/2010/05/19th-c-immigration-to-south-africa.html

Caithness at Eling, Marchwood and Totton

molegenealogy.blogspot.com/2013/09/caithness-at-eling-marchwood-and-totton.html

Mariners: The First Rung of the Ladder

molegenealogy.blogspot.com/2013/09/mariners-first-rung-of-ladder-2.html

More on Anglo-Boer War Ancestors

molegenealogy.blogspot.com/2010/03/more-on-anglo-boer-war-ancestors.html

19th c German Immigrants in South Africa

molegenealogy.blogspot.com/2010/02/more-19th-c-german-immigrants-in-south.html

Pruning the Family Tree

molegenealogy.blogspot.com/2011/07/pruning-family-tree.html

Passenger Lists as a Primary Source

molegenealogy.blogspot.com/2011/06/passenger-lists-as-primary-source-in-sa.html

Your Ancestor in the South African Constabulary

molegenealogy.blogspot.com/2010/03/your-ancestor-in-south-african.html

Identifying Uniforms in Photographs

molegenealogy.blogspot.com/2010/03/identifying-uniforms-in-photographs.html

Passengers to Natal 1865

molegenealogy.blogspot.com/2012/06/passengers-to-natal-1865.html

19th c Immigration to South Africa

molegenealogy.blogspot.com/2010/05/19th-c-immigration-to-south-africa.html

Caithness at Eling, Marchwood and Totton

molegenealogy.blogspot.com/2013/09/caithness-at-eling-marchwood-and-totton.html

Mariners: The First Rung of the Ladder

molegenealogy.blogspot.com/2013/09/mariners-first-rung-of-ladder-2.html

Thursday, November 21, 2013

A mariner's widow at Totton 1826-1889 1

When James Caithness died suddenly of an asthma attack in

1826, his widow Ann, aged 30, was expecting their fifth child (Charles). The

four older children were James Ramsay b 1815, George b 1818 (1817 on his Master's 'ticket'), Mary Ann b 1820

and William b 1824.

It was a dire situation for any woman but Ann rose to the challenge, making successful application for her two eldest boys to attend theRoyal Hospital

School , Greenwich , to be trained as mariners and

receive an education.

The first ten, even twenty, years of Ann's widowhood must have been extremely difficult. Whether she would have continued to receive James's naval pension of 20 pounds a year has yet to be established. By 1841 William, then 17, was working as a servant in Redbridge, in the parish of Millbrook, a small village in South Stoneham union. (The entry was hidden under the surname Kaithness.) His mother, aged 45, was living on her own in Totton. Charles was nearby, a baker’s apprentice at 15.

It was a dire situation for any woman but Ann rose to the challenge, making successful application for her two eldest boys to attend the

|

Map shows Totton, Eling (and its mill), Redbridge, Millbrook and Marchwood |

|

| St Mary's, Southampton |

George was pursuing his career in the mercantile marine, serving as an apprentice, seaman and mate during the decade 1830-1840. Charles was a journeyman baker by the late 1850s and, in keeping with the family's maritime associations, became a ship’s baker; he was with the Peninsular and Oriental line by 1861. They were all making their way and forging their own lives.

There’s a rumour that William visited South Africa in

1853 but documentary evidence of this is lacking. In March 1851 he was with his

mother in Millbrook village, working as a labourer. Nothing changed by 1861,

other than their ages: Ann was then sixty-five and William thirty-five. It was the last Census in which he would be listed.

It’s all very well tracing ancestors using the Census: the

entries do provide milestones to hang their story on, giving some indication of where they lived, who was in the household and

their occupations, but the important years between could remain invisible

history unless other extant records are covered. The possibilities are endless:

vestry minutes, churchwardens’ accounts, settlement papers, monumental

inscriptions, apprentice bindings, muster rolls, poll books and many more

sources.

| Ann and William at Mousehole, Millbrook, Hampshire: 1861 Census |

Equally vital – and just as fascinating - is background and

contextual research: the setting in which the ancestors found themselves, their

social scene, their neighbourhood, external influences such as economics,

politics, epidemics and wars – even the weather – in fact everything that

affected their lives, bringing us a closer understanding of their

circumstances, actions and experiences. This makes the difference between a

grayscale picture and one in glorious colour.

To be continued

|

Eling Riverside Walk |

To be continued

Wednesday, October 23, 2013

Middies and loblollys: Royal Navy

Midshipmen, ‘middies’, or

‘young gentlemen’, were officer cadets, usually drawn from middle to upper

echelons of British society and with ‘good family’ and some education behind

them.

Like less privileged sailors

they started their naval careers at a very early age - 9 was not uncommon - and learned navigation

and other branches of seamanship while serving at sea. The term midshipman

derived from the area on board ship, ‘amidships’. By the Napoleonic era

(1793-1815) a midshipman would have served at least three years as a volunteer

or able seaman, or as an officer’s servant. After that he would take the

examination for lieutenant which theoretically would make him eligible for

promotion. However, patronage was an important factor: a good patron could make

all the difference to a young gentleman’s progress in the navy.*

Like less privileged sailors

they started their naval careers at a very early age - 9 was not uncommon - and learned navigation

and other branches of seamanship while serving at sea. The term midshipman

derived from the area on board ship, ‘amidships’. By the Napoleonic era

(1793-1815) a midshipman would have served at least three years as a volunteer

or able seaman, or as an officer’s servant. After that he would take the

examination for lieutenant which theoretically would make him eligible for

promotion. However, patronage was an important factor: a good patron could make

all the difference to a young gentleman’s progress in the navy.*

Though advantaged in

comparison with the ordinary sailor the middies learnt the ropes in a harsh

school, the general conditions and the horrors of combat soon eclipsing any

romantic ideas they may have had about the navy, its heroes, glorious victories and prize

money.

This world is well-presented

in the Hornblower series of films based on the works of C S Forester and also

in Master and Commander: the Far Side of the World, from the Aubrey-Maturin

novels by Patrick O’Brian. The events depicted also provide a glimpse of

conditions for ordinary ratings who hauled ropes and manned guns and for the

able seamen who did the essential work aloft.

|

| Going aloft |

If James Caithness began his

career as a powder monkey he may have graduated to loblolly boy, assisting the

ship’s surgeon by performing various gruesome tasks such as cleaning up after operations.

With time and experience, given that he survived, he would rise to AB (Able

Seaman).

|

| Sailor 1799: James Caithness probably wore a similar outfit |

|

| Uniform Royal Navy 18th c National Maritime Museum, Greenwich |

* for more on patronage and promotion see www.thedearsurprise.com/?p=1314

Saturday, September 14, 2013

Souvenir Saturday: Caithness at Cracknore Hard

James Caithness the Ferryman

Cracknore Hard 1831 (etching by David Charles Read)

Acknowledgement:

Tom Sheldon

Cracknore Hard 1831 (etching by David Charles Read)

A

fine view of the ferry station at Cracknore Hard in Southampton

estuary on the south bank of the River Test. From here the ferry would take passengers

to West Quay, Southampton.

On

20 August 1815 at the baptism of his son James (Ramsey), James Caithness snr’s

occupation is given as ‘waterman’ and his place of abode as Cracknore Hard. By

1820 when his daughter Mary Ann is baptized – like her elder brothers James and

George (1818) at St Mary’s Church, Eling, Hampshire – James snr is ‘ferryman’.

The

coastal landscape at Cracknore Hard at that time would have looked much as

shown in this etching. James was then an experienced mariner having served on various ships before being discharged

from the Royal Navy at the end of the Napoleonic Wars. Shockingly, he had also been a prisoner of war in France

After

surviving for nearly a decade enduring dreadful privations, if contemporary

accounts are to be believed, James must have found a welcome sanctuary in the

expansive, peaceful stretches of the estuary and the comforts of home and

family.

Southampton

Water 1831 (etching by David Charles

Read)

A

spacious impression of Southampton Water by the same artist. No doubt James

Caithness was familiar with this vista. The broad horizon and low-lying land- and waterscape is reminiscent of Holland. It's also similar to the area alongside the Solway Firth, Cumberland, where William Bell (Mary Ann Caithness's husband-to-be) was learning to be a mariner at the beginning of the second decade of the 19th c.

The Book of Trades or Library of Useful Arts 1811 offers the following:

Watermen are such as row in boats and ply for fares on various rivers. A waterman requires but little to enable him to begin his business, viz. a boat, a pair of oars and a long pole with an iron point and hook at the lower end, the whole of which is not more than twenty pounds. The use of the pole is to push off the boat from land; the hook at one end enables him to draw his boat to shore, or close to another boat.

Acknowledgement:

Tom Sheldon

Tuesday, September 10, 2013

Caithness, James Ernest (1839-1902) 1

Is it a mariner’s life for me?

James Ernest

Caithness was born at No.7 George Row, Bermondsey (just south of the River

Thames) on 17 May 1839. His father James Ramsey Caithness (1815-60), a Master Mariner, and

mother Elizabeth Watson nee Ridges (1815-51) had married the previous year in Southampton . James

had been both born & baptised as James Edward but decided he preferred the

middle name Ernest at some point during his life.

There was a

strong maritime tradition in his family. His grandfather James Caithness had seen action whilst serving in the

Royal Navy against the French in the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. His father James Ramsey and his uncle George

had received their education at the Lower

School

|

The Royal Hospital, Greenwich |

James Ramsey

Caithness decided to settle in South

Africa Cape Town or Port Elizabeth

Young James

Ernest was to witness the harsh realities of a mariner’s life. His father James Ramsey had his fair share of

accidents – through no fault of his own. The worst incident perhaps was in 1855

when one of James Ernest’s brothers, likely to have been Alfred Douglas, was

killed during a fire on board the ‘Flying Dragon’ whilst his father was in

command (the same ship had also caught fire the previous year under Captain

Carter off Simon’s Bay). James Ramsey

Caithness himself died in 1860 ‘after a long and painful illness’ aged 44.

Family oral

tradition mentions that James Ernest tried his hand at sheep farming in South Africa London Eureka

Guest Post by Tom Sheldon, 2 x great grandson of James Ernest Caithness

Photo portrait by kind permission of June B-R

Saturday, September 7, 2013

Souvenir Saturday: Caithness Scorey 1814

|

St Mary's Church, Totton, Eling, Hampshire James Caithness snr. (1786-1826) married Ann Scorey (1796-1889) here on 30 June 1814 |

Acknowledgement:

Photograph by Peter Hay

St Mary the Virgin is the oldest of the churches in the Totton area. Several years ago during the reordering of the church excavations, part of a Celtic cross dating back to the 9th (possibly the 6th) century was found. The site of St Mary's has been a place of Christian worship since that date.

Today the church stands on the hill looking out over the bay to the container port on the Southampton side of Millbrook. On this side, not far away is the expanse and beauty of the New Forest. St Mary's finds itself at a threshold between the industry of Southampton and the quiet of the forest. Within the tension of both lies the possibility of both old and new. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Totton_and_Eling

Monday, August 5, 2013

Ships and Mariners: 19th c Cape and Natal 1 Bell

‘…those

proud ones swaying home

With mainyards backed and bows a cream of foam,

Those bows so lovely-curving, cut so fine,

Those coulters of the many-bubbled brine …’

With mainyards backed and bows a cream of foam,

Those bows so lovely-curving, cut so fine,

Those coulters of the many-bubbled brine …’

Masefield’s

vision is rose-coloured: seafaring could be a grim business.

On 2 July 1831,

the South African Commercial Advertiser reported a fatal maritime accident

which had occurred on the 20 June at Algoa

Bay

Before the Schooner Conch got under weigh … a brass gun was fired for the purpose of warning the Passengers to embark, when unfortunately the gun burst, and severely wounded the seaman who fired the gun. He was immediately taken on shore, and it was found necessary to amputate one of his legs, but he expired on the following day.We aren’t told the name of the dead man.

At this

date, Conch was not under the command of Captain William Bell, who only a month

earlier had been serving as 2nd officer on Thorne, which ship went

aground near Robben Island on 18 May 1831. From information gathered in Cape press shipping columns it seems likely that Captain Cobern was master of the Conch at the time of the gruesome event described

above. Cobern may have held that command since the death, significantly aged

only 37, of the wonderfully-named Captain Telemachus Musson ‘late of the

Schooner Conch’ on 1 March 1827.* The life of a merchant mariner was erratic, dangerous

and frequently short.

In October

1834, there is reference to Captain A Humble sailing Conch from Knysna to Table Bay . Another name that crops up is T Bosworth. These captains

were all operating under the auspices of ship’s agent James Smith and by at least

January 1837 William Bell was added to the stable.**

|

| Conch 1834 |

Schooners were

a favourite type of coasting vessel. Rigged with fore-and-aft sails on two or

more masts, they required a comparatively small crew and were thus more

economical to run than were square-rigged

vessels. Speedy and of low draught, enabling them to enter shallow harbours, schooners carried some passengers but their most important function was

transporting a variety of colonial produce.

Conch was about 100 tons; some sources describe her as a brigantine, though this indicates a square-rigged vessel, which she was not. Her Port of Registry was Cape Town. Her regular Ports of Call were Cape Town, Algoa Bay, Mossel Bay, St. Helena, Knysna, Saldanha Bay, Rio de Janeiro, Simon's Bay, Plettenberg Bay, Breede River, Struys Bay, Port Beaufort, Waterloo Bay. However, under Bell's command she visited Natal more than once, leading to his knowledge of that harbour when his assistance was required during the conflict in 1842.

Conch was about 100 tons; some sources describe her as a brigantine, though this indicates a square-rigged vessel, which she was not. Her Port of Registry was Cape Town. Her regular Ports of Call were Cape Town, Algoa Bay, Mossel Bay, St. Helena, Knysna, Saldanha Bay, Rio de Janeiro, Simon's Bay, Plettenberg Bay, Breede River, Struys Bay, Port Beaufort, Waterloo Bay. However, under Bell's command she visited Natal more than once, leading to his knowledge of that harbour when his assistance was required during the conflict in 1842.

Ships were

owned and registered in part shares – 64 shares being the customary number,

supposedly because ships traditionally had 64 ribs.

*Possibly Telemachus Giles Musson/Masson

b 1781, son of a Chief Mate in the East India Company’s service and the widowed

Mrs Maria Musson; East India Company

Pensions 1793-1833. Also: KAB MOIC Vol 2/323 Ref 1143 Liquidation and Distribution Account.

** John Owen Smith later took over as ship's agent.

** John Owen Smith later took over as ship's agent.

Thursday, June 27, 2013

Coastal Ships, Mariners and Visitors: Cape Colony 19th c 2

PORT ELIZABETH IN THE 1830s

Arriving eventually at Algoa Bay after an uncomfortable voyage up the coast from Table Bay, Cornwallis Harris was not favourably impressed with what he found:

THE SCOREY AND CAITHNESS FAMILIES

Of greater interest than Cornwallis Harris’s opinion of Port Elizabeth and its available horseflesh is his casual remark, ‘We tarried a week at Mrs. Scorey’s fashionable hotel.’

This hostelry, previously the home of Captain Moresby and said to be the first private house built in Port Elizabeth, was called Markham House. It had changed hands and as a hotel had been run successfully by a lady named Anne Robinson. She had married in 1829 at Port Elizabeth one James Scorey, master of the schooner Flamingo. (Scorey is noted for having put up a flagstaff for the use of the port in 1829.) At the time of Cornwallis Harris’s visit in 1836 Anne was Mrs. Scorey and her inn with its elevated position and riverside garden continued to be popular. The open space in front of the hotel was known to local residents as Scorey’s Place. The hotel was doing well enough for James Scorey to retire from the sea in 1834.

James Scorey was the uncle of Mary Ann Caithness (b 1820). Mary Ann’s mother (confusingly another Ann Scorey, b 1796) had married James Caithness snr (Master Mariner) at Eling, Hampshire in 1814. James Ramsey Caithness jnr. (b 1815) following in his father's footsteps and perhaps encouraged by reports sent ‘home’ by James Scorey, took up residence at the Cape and plied the coastal trade. He became captain of the brig Lady Leith (which met with disaster in 1848). Henry George Caithness commanded at various dates the vessels Louisa and Fame.**

WILLIAM BELL

Part of this close-knit colonial maritime circle was Cumbrian-born William Bell, master of the schooner Conch, who would marry Mary Anne Caithness at Port Elizabeth in June 1838. It is possible that William and Mary Anne, the latter out on a visit from England, met at Scorey’s Hotel and that romance blossomed as the two walked together in the pleasant gardens reaching down to the Baakens River. The name Ann Scorey (i.e. wife of James Scorey) is given as one of the witnesses at the Bell/Caithness wedding. The groom was 31, the bride 18 and they were married by special licence granted by Major General Napier.*

JOHN OWEN SMITH AND GEORGE CATO

William Bell and James Ramsey Caithness had the same ship’s agent, John Owen Smith. And here emerges another familiar name, George Cato, who from 1834 worked as manager for J O Smith. Descended from a Huguenot family who fled to England to escape religious persecution in France in the 17th c, Cato’s father and family had arrived at the Cape in 1826. The sudden death of Cato snr in 1831 (he is said to have been killed by an elephant) meant that George had to become a breadwinner. No doubt this enforced early maturity helped Cato to develop his entrepreneurial skills and other natural abilities which he put to good effect from that time onwards.

Cato became Bell’s lifelong friend, later rising to prominence in Natal as Mayor of Durban in 1850s. During the 1830s Cato was operating for Smith in the salt beef trade and in 1838 sailed the vessel Trek Boer up the east coast carrying goods for trade with the trekkers – Dutch frontier farmers who had left the Cape Colony and established themselves at Port Natal. Although neither Bell nor Cato could foresee future events, they were both to become embroiled in the conflict which would arise at Natal between the trekkers and the British in 1842.

SIGNIFICANCE OF MIDDLE NAMES

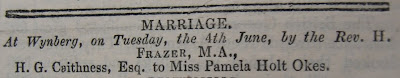

Local newspaper announcements emphasise the network of family connections so much a feature of colonial life. On 29 July 1839 Mary Ann and William Bell’s first child, a daughter, was christened Mary Ann Elizabeth Pamela Bell at Wynberg, Cape. The officiating minister was the Rev. Holt Okes, whose daughter Pamela had married Henry George Caithness a few weeks earlier.

This useful nugget answers the question of why the middle name Pamela was chosen for the Bell baby. Her other middle name, Elizabeth, was in honour of William Bell’s mother, Elizabeth Millican.

William and Mary Ann would produce a dozen children between 1839 and 1862, the last, Alice Millican Bell, born in Durban when Mary Ann was aged 42. Despite child-bearing and rearing taking up much of her time, Mary Ann is believed to have accompanied her husband on at least one voyage to Rio de Janeiro in the 100 ton schooner Conch.

*George Thomas Napier (1784-1855) Major General in 1837, later knighted, was Governor and Commander-in-Chief of the army in the Cape Colony from 1839-1843. The two major events during his period as Governor were the abolition of slavery and the removal of the trekkers from Natal following the conflict of 1842.

** Current research into the Caithness mariners and their precise relationship to each other continues. James Ramsey Caithness had a brother, George, also a mariner, but he couldn't have been sailing in Cape waters until after 1850. Henry George Caithness, however, disappears from Cape records a decade earlier.

Thanks to Anita Caithness for her input on Markham House/Scorey's Hotel. Also to Margaret Harradine for her article 'Port Elizabeth's First Hotel'.

|

| Port Elizabeth Algoa Bay by Thomas Baines |

‘Algoa Bay is exceedingly open and exposed and the anchorage very insecure. During high winds ships not unfrequently go on shore, a tremendous surf often rendering it dangerous, and at times even impossible, for boats to land. We were fortunate in being able to prevail on the Port Captain to take us ashore in his barge … The town of Port Elizabeth, though rapidly increasing, does not consist of above one hundred and fifty houses. It is built along the sea-shore on the least eligible site that could have been selected.’In this unpromising spot Cornwallis Harris and party attempted to buy horses to continue their journey inland.

‘We understood (these could) be obtained in the adjoining districts in considerable numbers, and of an excellent quality. It was with inconceivable difficulty, however, that we at length succeeded in procuring two miserable quadrupeds, that appeared to have scarcely sufficient stamina to carry us to Graham’s Town. The recent (Frontier) war having trebled the price of every thing, and of live stock in particular, the demands upon us were exorbitant.’

THE SCOREY AND CAITHNESS FAMILIES

Of greater interest than Cornwallis Harris’s opinion of Port Elizabeth and its available horseflesh is his casual remark, ‘We tarried a week at Mrs. Scorey’s fashionable hotel.’

This hostelry, previously the home of Captain Moresby and said to be the first private house built in Port Elizabeth, was called Markham House. It had changed hands and as a hotel had been run successfully by a lady named Anne Robinson. She had married in 1829 at Port Elizabeth one James Scorey, master of the schooner Flamingo. (Scorey is noted for having put up a flagstaff for the use of the port in 1829.) At the time of Cornwallis Harris’s visit in 1836 Anne was Mrs. Scorey and her inn with its elevated position and riverside garden continued to be popular. The open space in front of the hotel was known to local residents as Scorey’s Place. The hotel was doing well enough for James Scorey to retire from the sea in 1834.

James Scorey was the uncle of Mary Ann Caithness (b 1820). Mary Ann’s mother (confusingly another Ann Scorey, b 1796) had married James Caithness snr (Master Mariner) at Eling, Hampshire in 1814. James Ramsey Caithness jnr. (b 1815) following in his father's footsteps and perhaps encouraged by reports sent ‘home’ by James Scorey, took up residence at the Cape and plied the coastal trade. He became captain of the brig Lady Leith (which met with disaster in 1848). Henry George Caithness commanded at various dates the vessels Louisa and Fame.**

|

| Scorey's Hotel is the large building at left, with the gardens in the foreground leading down to the river. |

WILLIAM BELL

Part of this close-knit colonial maritime circle was Cumbrian-born William Bell, master of the schooner Conch, who would marry Mary Anne Caithness at Port Elizabeth in June 1838. It is possible that William and Mary Anne, the latter out on a visit from England, met at Scorey’s Hotel and that romance blossomed as the two walked together in the pleasant gardens reaching down to the Baakens River. The name Ann Scorey (i.e. wife of James Scorey) is given as one of the witnesses at the Bell/Caithness wedding. The groom was 31, the bride 18 and they were married by special licence granted by Major General Napier.*

JOHN OWEN SMITH AND GEORGE CATO

William Bell and James Ramsey Caithness had the same ship’s agent, John Owen Smith. And here emerges another familiar name, George Cato, who from 1834 worked as manager for J O Smith. Descended from a Huguenot family who fled to England to escape religious persecution in France in the 17th c, Cato’s father and family had arrived at the Cape in 1826. The sudden death of Cato snr in 1831 (he is said to have been killed by an elephant) meant that George had to become a breadwinner. No doubt this enforced early maturity helped Cato to develop his entrepreneurial skills and other natural abilities which he put to good effect from that time onwards.

Cato became Bell’s lifelong friend, later rising to prominence in Natal as Mayor of Durban in 1850s. During the 1830s Cato was operating for Smith in the salt beef trade and in 1838 sailed the vessel Trek Boer up the east coast carrying goods for trade with the trekkers – Dutch frontier farmers who had left the Cape Colony and established themselves at Port Natal. Although neither Bell nor Cato could foresee future events, they were both to become embroiled in the conflict which would arise at Natal between the trekkers and the British in 1842.

SIGNIFICANCE OF MIDDLE NAMES

|

| Marriage announcement: H G Caithness to Pamela Holt Okes South African Commercial Advertiser June 15 1839 |

This useful nugget answers the question of why the middle name Pamela was chosen for the Bell baby. Her other middle name, Elizabeth, was in honour of William Bell’s mother, Elizabeth Millican.

William and Mary Ann would produce a dozen children between 1839 and 1862, the last, Alice Millican Bell, born in Durban when Mary Ann was aged 42. Despite child-bearing and rearing taking up much of her time, Mary Ann is believed to have accompanied her husband on at least one voyage to Rio de Janeiro in the 100 ton schooner Conch.

*George Thomas Napier (1784-1855) Major General in 1837, later knighted, was Governor and Commander-in-Chief of the army in the Cape Colony from 1839-1843. The two major events during his period as Governor were the abolition of slavery and the removal of the trekkers from Natal following the conflict of 1842.

** Current research into the Caithness mariners and their precise relationship to each other continues. James Ramsey Caithness had a brother, George, also a mariner, but he couldn't have been sailing in Cape waters until after 1850. Henry George Caithness, however, disappears from Cape records a decade earlier.

Thanks to Anita Caithness for her input on Markham House/Scorey's Hotel. Also to Margaret Harradine for her article 'Port Elizabeth's First Hotel'.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)