|

Anglo-Boer War: Fry's Queen Victoria Christmas/New Year Gift Tin (chocolate for the troops). Text in the Queen's handwriting reads: I wish you a Happy New Year, Victoria. |

Pages

Tuesday, December 31, 2019

New Year's Greetings from Queen Victoria

Saturday, December 21, 2019

Thursday, December 19, 2019

Christmas Greetings

Saturday, December 14, 2019

A Natal Settler Christmas: 1853 and 1865

For British settlers who came to Natal in the 1850s, Christmas was very different from those they were used to ‘back home’. Despite the unusual experience of 25 December occurring in the midst of summer heat, most families tried to retain aspects of their familiar seasonal traditions – turkey, roast beef, plum pudding and as many trimmings as possible. This would be a pattern followed by generations of Natal settler descendants.

Eliza Feilden, emigrating with her husband Leyland on the Jane Morice and acquiring the farm Feniscowles in Durban, wrote letters home during their five year sojourn in the Colony. When the Feildens returned to England, Eliza published her letters together with selections from her journal (the original journal is held at the Local History Museum, Old Court House, Durban). The result is a fascinating, illustrated account of settler life in Natal and more particularly a settler wife’s reactions to her new environment.

Eliza wrote in December 1853:

I am sitting on the door-steps under our deep roof, sheltered from the intense heat of the sun this scorchingly hot day, the thermometer 78 degrees in our cool, shady, and airy room. I walked over the ploughed field at two o’clock, seeking for my husband, and the ground burnt my feet through my shoes …

The farm is looking quite beautiful again … the arrowroot and sugar-canes as well as they can look … I do think the climate – lovely and charming as it is – very wearing and enervating, with all the work that has to be done, but I enjoy it.

We had no plum pudding on Christmas Day. We ate our roast beef and calabash and our papaw tart with relish, and drank all your healths (i.e. the family in England). We rode into church in the morning, and partook of the sacrament. Most people made a holiday. We were invited to a picnic, but rode home quietly, and Leyland … planted arrowroot all the afternoon.

Extract from My African Home, or Bush Life in Natal 1852-7 by Eliza Whigham Feilden, 1887 Sampson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington, London. A reprint edition was published fairly recently.

Christmas in Natal 1865

On Christmas Eve 1865, Sidney Turner, a pioneer of the Natal South Coast and Pondoland, wrote from the Lower Umzimkulu Drift:

I should have gone up to the Umzinto till Christmas, but am expecting the Governor and suite to be here every day … They were to cross the Upper Drift and to come back to Durban (120 miles away) by the lower road, it will be an event if they do …

December 25th, Evening, 9 o’clock

I hope you have been enjoying your plum pudding and cattle-plagued beef just at the same time that I was eating a hot fowl, sweet potatoes, French beans and cabbages, with a dessert of peaches, granadillas, pineapples and cucumber. I have some beauties in my garden. It was three o’clock when my dinner began, one o’clock with you. I drank all your healths in a glass of rum and water, in spite of my teetotal pledge, as that isn’t to be expected to be kept when I have to wish a merry Christmas and happy New Year to those 10, 000 miles away.

I have had lots of swimming today, while perhaps you have been skating. I should like to try to swim from Dover to Calais if ever I get Home.

In a letter to his parents at New Year Sidney remarked that he had thought about them all on Christmas Day. ‘ … It was the day before that on which I shot the lion, and I had forty miles to ride to catch the wagon’ - hardly reassuring news for his family over the festive season.

A year later Sidney was able to report that his new house was ready to be occupied: it had

a large sitting-room, two bedrooms, pantry and store, with verandah all round. It will seem really like getting to civilization when I go into it. There is a splendid view ... this is likely to be the first time since coming out that Christmas will seem to be really Christmas; not so much because of plum pudding or beef, but that it is the first time that I have felt really at home and comfortable.

This in spite of soaring temperatures. But though Sidney remains cheerful there is, as in most emigrant journals and correspondence, nostalgia for the old country and people left behind. Christmas morning was ‘awfully hot’ and ‘would, I think, be almost too much for Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego …'.

My plum pudding came to a bad job … so I ate beef for dinner, and had the pudding out and baked it in a tin dish till 7 p.m. but it still kept a sort of paste. I have just been eating some of it with milk and sugar, but it sticks to the top of your mouth much worse than the old stickjaw we used to get at school … You are now no doubt getting ready for dancing … Couldn’t I, and wouldn’t I, just have a go were I at Home at the present minute.’

Turner spent forty years in South Africa between 1864 and his death in 1901. He made a happy marriage, his wife Bella surviving him for about thirty years; they had twenty-two grandchildren. Perhaps his most exciting and notable contribution to history, apart from his valuable letters, was his interest in the wreck of the East Indiaman, Grosvenor, of which he salvaged several relics.

Extracts from Portrait of a Pioneer: The Letters of Sidney Turner from South Africa 1864-1901, selected and edited by Daphne Child (MacMillan South Africa, 1980).

The originals, as well as Turner's Grosvenor relics, are held in the Local History Museum, Old Court House, Durban.

Thursday, December 12, 2019

Christmas in the 1860s - and where did the Christmas tree originate?

It wasn’t until the time of Queen Victoria that celebrating Christmas by bearing gifts around a fir tree became a worldwide custom. In 1846, Queen Victoria and her German husband Albert were sketched in the Illustrated London News standing with their children around a Christmas tree at Windsor Castle. German immigrants had brought the custom of Christmas trees to Britain with them in the early 1800s but the practice didn’t catch on with the locals. After Queen Victoria, an extremely popular monarch, started celebrating Christmas with fir trees and presents hung on the branches as a favor to her husband, the layfolk immediately followed suit.

Long before Christianity appeared, people in the Northern Hemisphere used evergreen plants to decorate their homes, particularly the doors, to celebrate the Winter Solstice. On December 21 or December 22, the day is the shortest and the night the longest. Traditionally, this time of the year is seen as the return in strength of the sun god who had been weakened during winter — and the evergreen plants served as a reminder that the god would glow again and summer was to be expected.

The solstice was celebrated by the Egyptians who filled their homes with green palm rushes in honor of the god Ra, who had the head of a hawk and wore the sun as a crown. In Northern Europe, the Celts decorated their druid temples with evergreen boughs which signified everlasting life. Further up north, the Vikings thought evergreens were the plants of Balder, the god of light and peace. The ancient Romans marked the Winter Solstice with a feast called Saturnalia thrown in honor of Saturn, the god of agriculture, and, like the Celts, decorated their homes and temples with evergreen boughs.

During the 16th century, the late Middle Ages, it was not rare to see huge plays being performed in open-air during Adam and Eve day, which told the story of creation. As part of the performance, the Garden of Eden was symbolized by a “paradise tree” hung with fruit. The clergy banned these practices from the public life, considering them acts of heathenry. So, some collected evergreen branches or trees and brought them to their homes, in secret.

The Christmas tree has come a long way from its humble, pagan origins, to the point that it’s become too popular for its own good. In the U.S. alone, 35 million Christmas trees are sold annually, joined by 10 million artificial trees, which are surprisingly worse from an environmental perspective. Annually, 300 million Christmas trees are grown in farms around the world to sustain a two-billion-dollar industry, but because these are often not enough, many firs are cut down from forests. We recommend opting for more creative and sustainable alternatives to Christmas trees.

Sunday, December 8, 2019

Umhlanga Light, Natal

|

Taken from the Lighthouse Bar, Oyster Box Hotel, Umhlanga |

A new light in Natal came into operation on 25 October 1954. This was the Umhlanga Lighthouse. Originally to be positioned in the vicinity of the swimming pool in the grounds of the Oyster Box Hotel, this idea was abandoned when in January 1953 13 inches of rain fell in less than 24 hours, causing heavy erosion close to the proposed site. It was decided to build the tower lower down nearer the sea on a solid rock foundation.

There were no festivities to mark the opening of the Umhlanga Light. It was brought into operation without the usual three months' notice to mariners being issued internationally. Warnings were however broadcast from the local maritime radio stations informing shipmasters of the introduction of this new aid.

Being unattended, this fully automatic light had to be equipped with an alarm system monitoring equipment failure and detecting fire or any unauthorised entry of the premises. At Umhlanga Rocks the alarm system is extended to the reception office of the Oyster Box Hotel, the proprietor reporting any alarm to the maintenance depot at Durban. So far the system has worked well.

Acknowledgement: Harold Williams, Southern Lights

New Year Resolutions for Family History

Even if you're not the type who makes New Year Resolutions, use this time of year to put together some goals for your family history research.

You may be spending a few hours with living relatives so get talking about what they know about the family and ask if they are able to identify any photos you have in your own collection. An unidentified photograph is the bane of a family historian's life.

If your relatives are actively involved in family history, get to know them better and make plans to meet and share information. They may even offer you copies of their photos or news reports. There's no time like the present.

Join a local family history society or start going to the family history library near you. People are usually very helpful and if it is new territory for you, volunteers will explain what is available and offer suggestions as to your research. It's worth attending talks, even if the topic is nothing to do with your own research, because inspiration may well strike as you listen to another person's ideas.

Check internet for any sign of books about your ancestor/s, or even books written by them. Often publications like these are out of print but there are people who specialise in finding copies of such books. Some may be available in their entirety on internet. Context is important so look for books about the era in which the ancestor lived, or the occupation he practised. What did he/she wear? Was their life comfortable or wretched? Is their residence marked on a map? Did an artist ever paint their house? Were they a settled family living in a certain district for many years? Or did they move about, perhaps in search of employment?

We all know by now (well, I hope we do) that there's more to family history than just names and dates. In this New Year, resolve to become the historian, the keeper of the family stories, collecting information, writing it down, preserving it. It is bound to add depth to your family history.

Most importantly, take the time to organise what you've already found out. Collate it in a publication for the family, start a blog to discuss the ancestry and share knowledge with others. Make sure that your descendants can easily access your lifetime's work when you're no longer here to answer their questions. Pass the flame on to your children and grandchildren so that there is continuity. They might not be all that keen now but believe me they will come to it as they get older and how grateful they'll be for your efforts.

Saturday, December 7, 2019

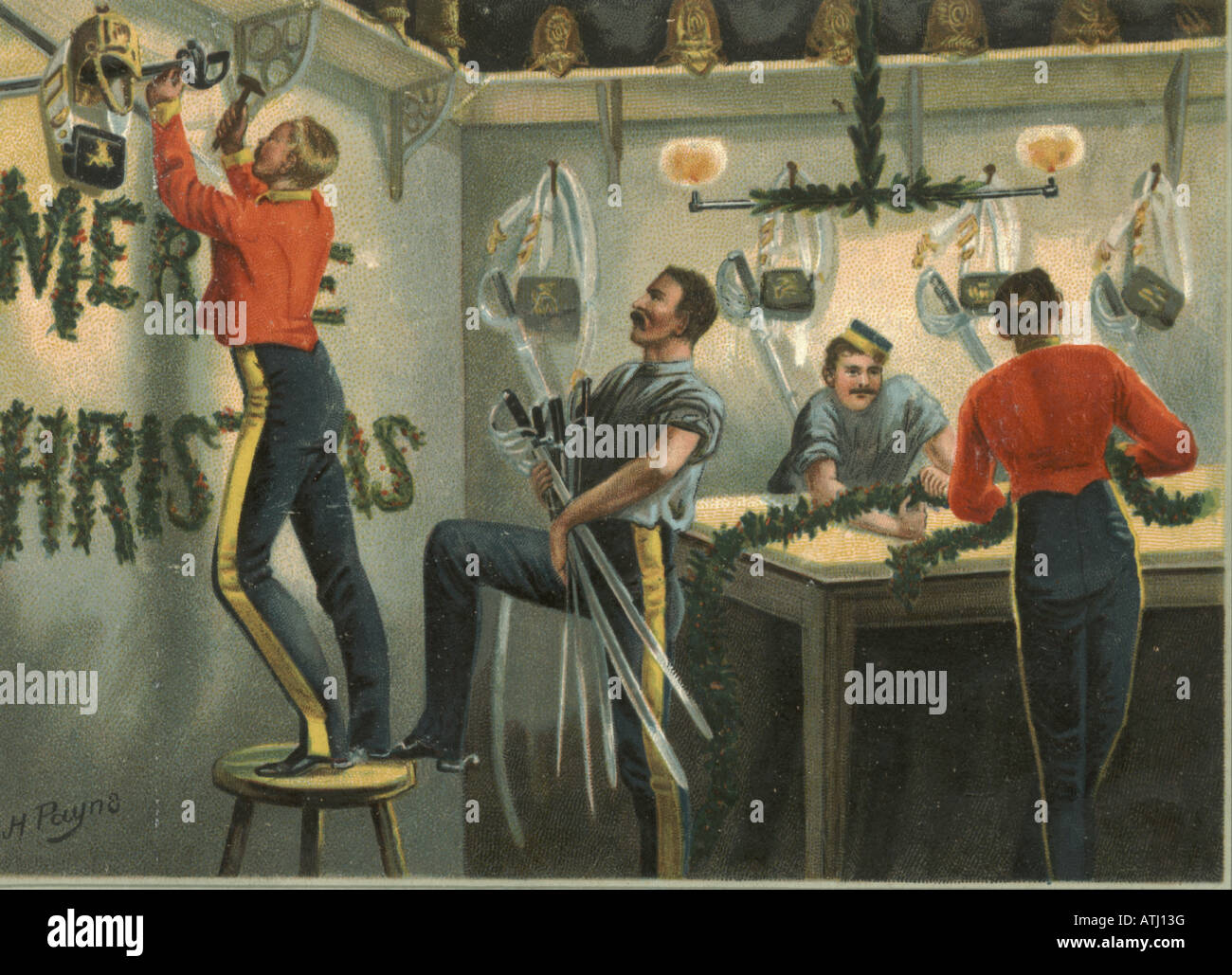

Christmas in the British Army, Victorian times.

Life in Victorian times was a tough undertaking; many men ‘escaped’ into the Army which was only marginally better in conditions and attitude. Christmas Day occurs every year and so Christmas Day 1879 dawned for the 2nd Btn Rutlandshires. Every season has its own sense of importance but preparations for this day of days takes a special turn in attitude and feeling. The officer class and enlisted men largely drop their class differences and become soldiers in barracks at Christmas. The General Return Of the Army in Victorian times shows some 223,000 enlisted men and many of these saw service in foreign lands for up to 20 years or so.

Differences between the officers and men were relaxed to a certain extent and preparations were underway for Dec 25th. Christmas Day in the Army was characteristically an organised affair with nothing left to chance. An air of solemnity was observed in the traditions of this day. Each man had a heavy burden of individual responsibility. Large quantities of both liquid and solid refreshments were procured, a great change from the Spartan diet usually endured by the men at this time.

The officers added to the fund with game and many a bottle to fuel the festive gatherings. The canteen funds swelled as this day approached. Barrels of ale, stout and porter appeared along with wine but little or no spirits. These supplies were taken in charge by the Colour Sergeant of each company and kept under lock and key until lunch on the 25th. As the great day loomed closer, the men were seen undertaking many a festive activity - stoning raisins for the puddings, divesting goose, duck and turkey of feathers, fashioning festoons of coloured paper and wreaths of holly. Men were detailed to act as messengers between the cookhouse and men’s barracks, the cooks having risen at an unseemly hour to make good the food to be served later in the day. At 6am reveille sounded on the barrack square by the duty bugler: Christmas Day had arrived!

Even before the last note had died away in the frosty air, the barracks of some 700 men were already a hive of activity, lights twinkling from many windows, scores of men moving along dimly lit passages to perform their necessary ablutions, once completed the rooms swept clean and dusted, beds made up as laid down in standing orders (I love that line). No drill today but Army Sunday routine observed. Once breakfast is over Church Parade takes over. ‘Fall In’ occurs at 10.30 am, many a soldier, though, being fortunate to have leave with families elsewhere. Today there are 350 men attending the Garrison Church, once everyone is inside the Chaplain commences the service. Being a former soldier himself he knows that a long service would not be the thing and delivers a more cheerful sermon than is usual.

On conclusion of the service the men are marched back to their barracks and dismissed, during their absence ‘cook’s mates’ have been busy getting the food ready, tables decorated, ceilings and walls gaily garnished with festive decorations. Much liquid of a beer nature is seen in every room. At 20 minutes to one the peal of the bugler playing ‘Come to the cookhouse doors me lads’ can be heard and the designated orderlies rush to the cookhouse to receive from their company cooks the food allocated to each mess. A batch of helpers is carving and serving up the now eagerly sought-after food. Food is taken to those on duty, and at one o’clock the bugle sounds again and the men sit down to start the feast.

Junior NCOs act as waiters to their comrades; cheerful demands for more turkey and duck ring out amongst the popping of corks and consumption of ale, beer barrels rapidly emptying. In comes the Company Colour Sergeant and calls ‘Attention!’, his keen ears having heard the clink of sword and spur on concrete floor: this heralds the visit of the Colonel, his adjutant and duty officer of the day. The Colonel wishes the men a Happy Christmas and turns to leave, this is the cue the Colour Sergeant was waiting for, as was the Colonel, knowing the procedure from past Christmases in the barracks.

‘Beg pardon, sir, the men would like to drink your health’. ‘Thank you, Colour Sergeant’. ‘Sherry or port, sir?’ - advancing to the two black bottles put aside for this very purpose, trying to recall what each one contained. ‘Whatever comes first, Colour Sergeant,’ retorts the Col. ‘Just a little though, if you please’, knowing he and his party will go through this more than once today. ‘A Company Attention!’ bellows the Colour Sergeant in a stentorian voice, ‘I propose the good health and long life of the Colonel and all the officers. Pte Jones, keep your hands off that plum duff for half a minute.’ Many heartfelt epithets are sounded, the Colonel is well loved by his men and his reply follows: ‘Men of A Company 2nd Rutlandshires, I am much gratified at the honour you have bestowed on me, enjoy yourselves and have a very happy Christmas.’ At this point he picks up his sword and leaves with his party to the next Company where this is repeated once again.

A great deal of toasting and well wishing continues throughout the day. Pte Jones tucks into his plum duff barely looking at the falling snow which appeared as if on cue. The Colonel retires to his quarters as do the officers and Sergeants to celebrate the Festive Day in their own manner. Much smoking and merriment ensue from the men, singers are encouraged to exercise their talents and problems are forgotten. At nightfall some of the men get into walking out dress and pursue the taverns of the town, the barracks now largely deserted. At 9:30 pm a roll call is taken and three quarters of an hour later the duty bugler plays ‘Lights Out’ on a crisp and white barrack square, thus proclaiming the official end to Christmas Day 1879.

Article by Graham Mason, Zulu War researcher and specialist.

Friday, December 6, 2019

Cape St Francis (Seal Point) Lighthouse

Wednesday, December 4, 2019

Passenger list: Golden Age Natal to Australia 1854

SHIPPING INTELLIGENCE Natal Mercury 12 July 1854

SAILED

July 12 - Golden Age, bq [barque]

W Jones - for Melbourne -

PASSENGERS

W Gallians

Mr Bayley and two children

H Baker, wife and two children

J Matters, wife and four children

J McGully

HJ Gale, wife and children

G St. Paul

J Forman

E Standish

Mrs Glover and three children

R Short

JS Erwood

J Cuthbert

E Dubois

J Clark

J Canning and wife

W Fuller

Charles Richards

Donald McPhail

R Mathew

Mrs Williams and two children

C Owen

T Poynton, wife and child

R Parker

Whitaway

Dineley

|

3-master barque similar to Golden Age |

Tuesday, December 3, 2019

Golden Age departure for Australia July 12 1854

There was much to-ing and fro-ing between Natal and Australia during the mid to late 19th c. Byrne settlers, disillusioned by conditions found in Natal, set off for the Australian fields. Some returned to try again. Australians were tempted by the South African gold and diamond fields, like those who sailed on the St Kilda. (See previous post.)

From the Natal Mercury 1 February 1854:

AUSTRALIA

The following extracts from the letter of a Natal Emigrant to Australia, received by the last Mail, may supply useful cautions to those who meditate a like perilous adventure.

'So long as you can gain anything more than a living, I wouldn't advise any married man to come here. Illness has been universal and a doctor's bill is no joke, I have incurred £5 myself, besides awful rheumatics. You know of course that Byrne is here, a storekeeper at the diggings. I was at Geelong, in Court, the other day when he was called as a witness, but in coming down he broke his leg, and couldn't appear. Rents are frightful, £100 per annum, for one room, and I have to live besides three miles from town at another rent.

Geelong is worse than Melbourne, nine inches in mud, in short the place and the climate is as bad as it can be, I have not met one who likes it. I believe you will soon have some of our people back again, some are at the diggings, but I have not heard of any doing well. The only persons who can ensure a living well, are carpenters, masons, and hard working labourers. Labourers who can stand any climate, - they get, - the former, £1 to £1 5s. and labourers 10s to 15s per day, but expenses are in proportion, nevertheless they do exceedingly well. Professional men are cheap enough and get cheaper every day.

'Trade is the way to make money. If I had capital I could double it every two months with safety. There is no comfort to be purchased. I send you a paper to show you the way we commit robberies here. We don't steal a few paltry pounds, but 2,300 ounces of gold. I may tell you that the escort from the diggings has been stopped, and 2,300 ozs of gold taken, the escort consisting of eight troopers, all shot dead but one; so says the report at present. They were attacked by 20 bushrangers, and shot from behind the trees. It is a common thing for one man to rob another of from £200 to £500. Last week £1,000 was taken from a digger.

My room is a back room, 10 x 9, stinks like a p....y: the yard behind is full of green slush and the front little better. When you hear grumblers in Natal, ask they if they are gaining a living; if they are, they are better a hundred times than those who are doing the same here. As for houses and stores they are not to be got. Talking of winter and not requiring warm clothing, I have nearly perished of cold. All that they have written about this colony as to climate is lies, lies, lies, from beginning to end. Every imaginable disease rides rampant here, and a few extra ones to boot. Grown people die, and children won't live.'

From the Natal Mercury 1 February 1854:

AUSTRALIA

The following extracts from the letter of a Natal Emigrant to Australia, received by the last Mail, may supply useful cautions to those who meditate a like perilous adventure.

'So long as you can gain anything more than a living, I wouldn't advise any married man to come here. Illness has been universal and a doctor's bill is no joke, I have incurred £5 myself, besides awful rheumatics. You know of course that Byrne is here, a storekeeper at the diggings. I was at Geelong, in Court, the other day when he was called as a witness, but in coming down he broke his leg, and couldn't appear. Rents are frightful, £100 per annum, for one room, and I have to live besides three miles from town at another rent.

Geelong is worse than Melbourne, nine inches in mud, in short the place and the climate is as bad as it can be, I have not met one who likes it. I believe you will soon have some of our people back again, some are at the diggings, but I have not heard of any doing well. The only persons who can ensure a living well, are carpenters, masons, and hard working labourers. Labourers who can stand any climate, - they get, - the former, £1 to £1 5s. and labourers 10s to 15s per day, but expenses are in proportion, nevertheless they do exceedingly well. Professional men are cheap enough and get cheaper every day.

'Trade is the way to make money. If I had capital I could double it every two months with safety. There is no comfort to be purchased. I send you a paper to show you the way we commit robberies here. We don't steal a few paltry pounds, but 2,300 ounces of gold. I may tell you that the escort from the diggings has been stopped, and 2,300 ozs of gold taken, the escort consisting of eight troopers, all shot dead but one; so says the report at present. They were attacked by 20 bushrangers, and shot from behind the trees. It is a common thing for one man to rob another of from £200 to £500. Last week £1,000 was taken from a digger.

My room is a back room, 10 x 9, stinks like a p....y: the yard behind is full of green slush and the front little better. When you hear grumblers in Natal, ask they if they are gaining a living; if they are, they are better a hundred times than those who are doing the same here. As for houses and stores they are not to be got. Talking of winter and not requiring warm clothing, I have nearly perished of cold. All that they have written about this colony as to climate is lies, lies, lies, from beginning to end. Every imaginable disease rides rampant here, and a few extra ones to boot. Grown people die, and children won't live.'

|

Australian Gold Diggings |

Sunday, December 1, 2019

St Kilda passengers: Australia to Natal and the Diamond Fields 1872

The Natal Mercury announced on 6 June 1872:

The St Kilda's Passengers met at the Immigration Aid Office yesterday afternoon, by invitation of the Directors. Of the latter there were present the Mayor, in the chair, and Messrs H Escombe, Goodliffe, Greenacre, Robinson, and Dacomb. Mr Escombe explained at length the objects of the Office, and an interesting conversation followed chiefly bearing on the best and cheapest way of reaching the Diamond Fields.

The new comers expressed much satisfaction with the attentions exhibited, and unanimously passed a resolution to that effect. It was finally decided to publish an advertisement, at the cost of the Office, calling for tenders for transport, and we refer wagon owners and carriers to the announcement elsewhere. Specimens of quartz from Marabastadt were pronounced excellent, but not sufficient in themselves to prove the existence of a gold field. Some of those present said they had seen in Australia similar specimens from reefs which were not payably auriferous.

We heartily trust that our new friends, of whom there are about seventy, will succeed in reaching the Fields quickly and cheaply, and that when there, success will crown their efforts. About twenty of those passengers came ashore on Saturday last. The vessel herself could not get in, as the wind was unfavourable.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)