James

Caithness’s pension details show that there was no gap in his naval service, yet

he drops out of sight for several years. This is because James was captured

along with all those on board the Calcutta and for

almost a decade was a prisoner-of-war in France

He was in his

twenties at the time of the battle in 1805 between the Magnanime and Calcutta

Their context takes

us along a byway of history largely forgotten today, an era when Europe was

held to ransom and tens of thousands of prisoners from various countries,

including Britain, were marched from pillar to post, left languishing in fortress

towns and dungeons or forced by deprivation and despair into renouncing their

own nationalities and joining Napoleon’s army.

Most British

subjects imprisoned, other than about 700 civilian detainees, were men of the

Royal Navy and mercantile marine captured, like James, during action at sea, or

when their ships were wrecked in French waters.

No evidence of precisely

where James Caithness spent his years in captivity has come to light. In all

likelihood he was taken initially to the distribution centre at Verdun

|

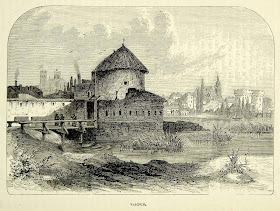

| Bitche: The Citadel |

Like many of them, he

may have tried to escape only to be caught and sent to the penal depot at

Bitche. Recapture after such attempts often meant death. The alternatives –

being sentenced to the galleys of Toulon

The experience

of a British prisoner-of-war in France Verdun

|

| Verdun on the River Meuse |

For the lower ranks

in the depots on the north-east frontier it was a different story. They were

subject to severe, overcrowded and insanitary conditions, often marched in all

weathers, scantily clad and sometimes shoeless, for hundreds of miles between

depots, and half-starved on a daily ration of a pound of bread and a meagre

portion of vegetables. Numbers died en route. Men who were ill or unable to

keep up with the line were left behind in rat-infested local gaols until,

inexorably, they were pushed on to another grim destination.

|

| Napoleon crossing the Alps, 1800: The Glory Years |

To be continued

No comments:

Post a Comment